The #1 Most Loved Program By Homeschool Families in America*

Education

At Home,

Made Easy

Courses, clubs, and support for your flexible education journey. All 100% free. Apply by November 10 for January 2026 start.

A One-of-a-Kind Program

A one-of-a-kind program

At OpenEd, we provide personalized learning experiences tailored to your child's needs. Our partnerships with innovative public schools ensure a robust educational foundation.

100% Tuition Free

We pay directly or reimburse parents for pre-approved educational expenses.

Freedom & Flexibility

Choose what, when, where, and how you want to learn.

Tutoring & Support

Tutoring and support when you need it. Clubs and community events to share the journey.

The OpenEd Program Is

Expanding Rapidly

A one-of-a-kind program

Now serving Arkansas, Kansas, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah. If you don't see your state, sign up for the waitlist to be the first to get notified when we arrive!

See How Other Families Use OpenEd

OpenEd helps you create the education that fits your child. Choose from our marketplace of programs, bring your own resources, or mix and match. You don't have to be an expert, you just have to know your child.

Open education is flexible

Rather than forcing families to choose between public/private, remote/on-site, part-time/full-time, large school/small school or any other approach, open education allows learners to take the best of all approaches and adapt it to their goals.

Open education is flexible

Rather than forcing families to choose between public/private, remote/on-site, part-time/full-time, large school/small school or any other approach, open education allows learners to take the best of all approaches and adapt it to their goals.

Three simple steps to

an open education

Three simple steps to an open education

Once you're officially enrolled, design your child's perfect education in three simple steps.

Click here to learn more about how it works.

Design your child’s education plan

Together, we’ll create a plan that matches your goals and your child’s interests. Want to mix traditional subjects with passion projects? Perfect. Prefer project-based learning? We’ve got you covered.

Access premium resources

Choose the curriculum, apps, clubs, and resources you'll use. Plus choose how to use your wallet of reimbursement for approved educational expenses.

Get support on your terms

We’re here when you need us – whether you want help choosing materials, planning projects, or just checking your approach. You decide how much support works for your family.

Meet Your Personal Support Team

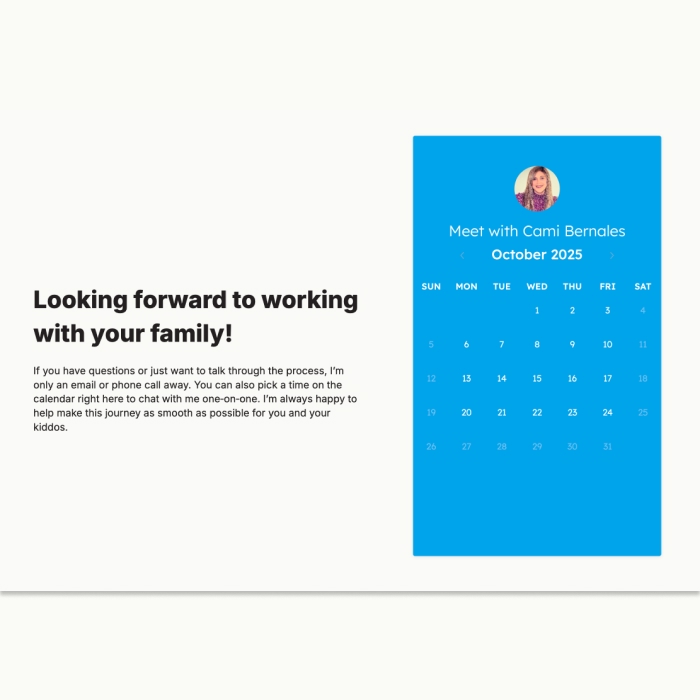

You're not doing this alone. When you join OpenEd, you get access to two amazing support professionals, many who are parents just like you.

Your Family Success Manager helps you navigate resources and solve challenges. They're in your corner, supporting you as the parent leading your child's education.

Your Child's Teacher will be their biggest cheerleader as they go through the program. They review learning logs, celebrate growth, and can help with day-to-day teaching recommendations.

Together, these two ensure both you and your child feel support(ed) and confident on this journey.

Already have questions? Contact us.

Ready to build an education that fits your child?

How we make this 100% FREE for families

We partner with innovative schools to offer this program at no cost to families. This means you get the best of both worlds: the flexibility of personalized learning with the benefits of traditional education.

Simple weekly updates from you help us maintain these benefits while giving you the freedom to create an education that fits your child.

Check with our team to learn what perks your family may get access to through our partnership:

- Special education services and support (IEP/504 plans)

- Sports & Clubs at your local boundary school

- Access to resources and technology tools

The most lov(ed) education program by homeschool families in America

Flexible Learning Options

of families are unlikely to return to traditional school after trying OpenEd.

Empowering Families Together

of families report being very satisfied

with OpenEd.

Tailored Education Opportunities

of parents recommend

OpenEd to their friends.

Transform(ed) Families

Discover how OpenEd transforms educational journeys. Our community of satisfied parents shares their experiences with personalized learning.

FAQs

Find answers to your most common questions about our educational services and support.

Find answers to your most common questions about our educational services and support.

OpenEd is a program designed to assist families in creating personalized learning experiences. We partner with innovative public schools to provide resources and support for at-home education. Our mission is to empower families to tailor education to their children's unique needs.

Enrollment for OpenEd is now open for the 2025-26 school year in Arkansas, Kansas, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah. We're rapidly expanding to serve more families. Join the waitlist to be notified when we launch in your state!

We offer reimbursement for approved educational expenses, making it easier for families to invest in their child's learning. To qualify, expenses must meet our guidelines and be submitted through our platform. This helps ensure that families can access the resources they need.

Any family interested in personalized education can enroll through OpenEd. We cater to various learning styles and needs, ensuring that every child has the opportunity to thrive. Our partnerships with public schools enhance the learning experience.

We provide a range of support services, including access to educational resources and guidance for parents. Our team is dedicated to helping families navigate the educational landscape. Whether you need curriculum advice or assistance with reimbursement, we're here to help.

Yes, families can change their educational plans as needed to better fit their child's evolving needs. We encourage open communication to ensure that your child's education remains effective and engaging. Our team is available to assist with any adjustments.

Still have questions?

We're here to help you! Contact us today.

Ready to Reserve Your Spot?

Join 17,000+ Families 100% FREE

.webp)