Playing with LEGO is More Valuable than Learning Algebra

Playing with LEGO is More Valuable than Learning Algebra

Playing with LEGO is More Valuable than Learning Algebra

I was homeschooled.

My mom really wanted to have a highly structured and rigorous curriculum for us. She didn’t.

She tried – lord knows the number of books she purchased at annual curriculum fairs – and we’d go through phases with a little more structure than others. But ultimately, she was raising three stubborn kids while also caring for a disabled husband (and just about anyone else we ever met who needed help… my mom is a wonderful woman who has a terrible time saying ‘no’).

The result is that my siblings and I didn’t do much consistent, structured learning. Today we might be called borderline “unschoolers”, but at the time nobody had heard the word. The most structure we had was in the daily and weekly chores we did to help keep up the house and yard and the fact that all three of us had paying jobs from age 10 or so on. (One of the benefits of not being in school all day is that you can work and earn money, though laws make this harder and harder.)

So what did we do? I would estimate that between the ages of 4 and 13, roughly half of my time on any given day was spent playing with LEGO. My mom used to feel guilty about this. Frankly, so did I. I was always a little worried that “real school kids” would be far ahead of me in their knowledge and skill and it might embarrass me some day. But that day never came. Real school kids suffered all day while I played LEGO, and by the time I went to school (one year in high school, and then college, neither of which were worth the cost) they were no better for it.

My mom would sometimes assign us math work through a textbook (Saxon Math. Even the name is ominous), which we would complete and grade on our own. I remember sitting at my desk and moving through “Algebra 1/2” as fast as I could, not caring or comprehending it. I’d grade it with the answer guide and fix errors, but mostly I was staring out the window at the excessively fat Squirrels of Milwood, who I’m pretty sure were running some kind of animal cartel. The fattest of them was an albino squirrel who was probably immortal. I called him The Godsquirrel. Where was I… oh yes, working on math problems…

That was pretty much how it would go. I’d get it out of the way (or not) and get back to my LEGO. Only later have I come to realize how much more valuable playing with LEGO was than the little math I did, or really any of the formal instruction I had. I remember nearly every Lego creation in detail and with great pride. In fact, give me some LEGO today I can still whip up a mean spaceship or watercraft if I do say so myself.

There are a few reasons I think playing with LEGO was much more valuable to me than pretending to learn from textbooks.

Confidence

Confidence cannot be given. It must be earned.

No cat poster telling you that you can do anything will really give you the self-esteem needed to pursue your goals with grit and determination.

Confidence comes by overcoming challenges and solving problems. Especially problems that are meaningful to you. Building entire cities with plastic blocks is time-consuming and can be very challenging. When you’re done, you get so much more than a gold star or a pat on the head or a lifeless word on a page that says, “Correct”. You get to see and touch and play with a tangible creation. Until you decide to destroy it, you have proof of your work and the challenges you overcame. (It’s doubly challenging when you have to dig through the Lego bin piece by piece so as not to be too loud and awaken your mom, who is probably on the phone helping someone downstairs, to the realization that you’re playing instead of working.)

Value Creation

In school, you’re rewarded for finding the right answers to questions you don’t care about. Neither does anyone else except (maybe) your teacher. In the marketplace where you’ll spend most of your life working and interacting, no one cares about whether you’re right on some arbitrary scale. They care about value creation. Playing with LEGO imparts this lesson. No kid gives two hoots about your method for finding and snapping together pieces. What matters is the beauty, originality, and functionality of the end result. Did you make something awesome? Everything else is negotiable and can be experimented with, but the ultimate test is whether you created something valuable to yourself and others. Not in theory, but in the real world. That’s a kind of “show your work” I can get behind.

Solve for X

Algebra is about figuring out puzzles when you don’t have all the pieces. But most kids don’t really know this and don’t really care. I didn’t. But I did love solving complex problems without having all the pieces… as long as those pieces were small bits of colored plastic. None of us had enough LEGO to build exactly what we envisioned in all the right colors and shapes. Especially back then when there were few custom pieces or crazy shapes. (Shakes cane at kids these days) You want to make a lightsaber? You’ve got to break some other pieces in half and improvise. Lego building is nothing but a series of complex design problems with a constant absence of the right pieces. I loved solving for X, as long as it was the X-Wing spacecraft.

Freedom

New sets come with instructions. Maybe you follow them once, maybe not at all. But eventually you’ll rip apart the prescribed design and create something new. There are no arbitrary rules, but it doesn’t mean there are no rules. Like the real world, some things are non-negotiable. The pieces have definite physical dimensions. You can break or color (or melt!) them sometimes, but only to a limited extent. You learn to work with the very few natural rules, but that with those you can create anything you want. A building that turns into an airplane that drops a bomb that’s really a submarine? No problem. The only limiting factors are your resources (of which you can acquire more if you save up your paper route money) and your imagination and skill. Learning to achieve goals when no one has assigned goals to you or methods for reaching them is the hardest thing for a schooled mind. It’s also the most valuable.

Change

Lego builds are not permanent. Siblings, friends, and mostly your own boredom drive you to tear down and recreate constantly. It’s an open-ended system. There is no once for all plateau or achievement. There is no Lego graduation. It’s a dynamic, non-linear world of possibility. Whatever you have built can and probably will be changed into something better. You’re never done. That mindset is powerful, and a strong shield against dangerous status quo bias and constructivist notions of the individual and society.

This is all playful (all the best things are) and anecdotal. If you want some deeper stuff about why playing with LEGO or any other self-chosen activity is superior to textbooks and schools and teacher-guided learning, check out the excellent work of Dr. Peter Gray.

Oh, and thanks mom. You never had it in you to be an authoritarian task-master, and that’s opened up the world to me.

————

Update: Some readers seem to have a difficult time getting the general point because of the specific title. The point of this post isn’t that always and everywhere for everyone LEGO play is more valuable than algebra. The point is that kids doing and learning things of their own choosing in their own way on their own time is more valuable than making them do stuff. Most kids will prefer LEGO to math. Let them play LEGO. Some may prefer math to LEGO. Let them do math.

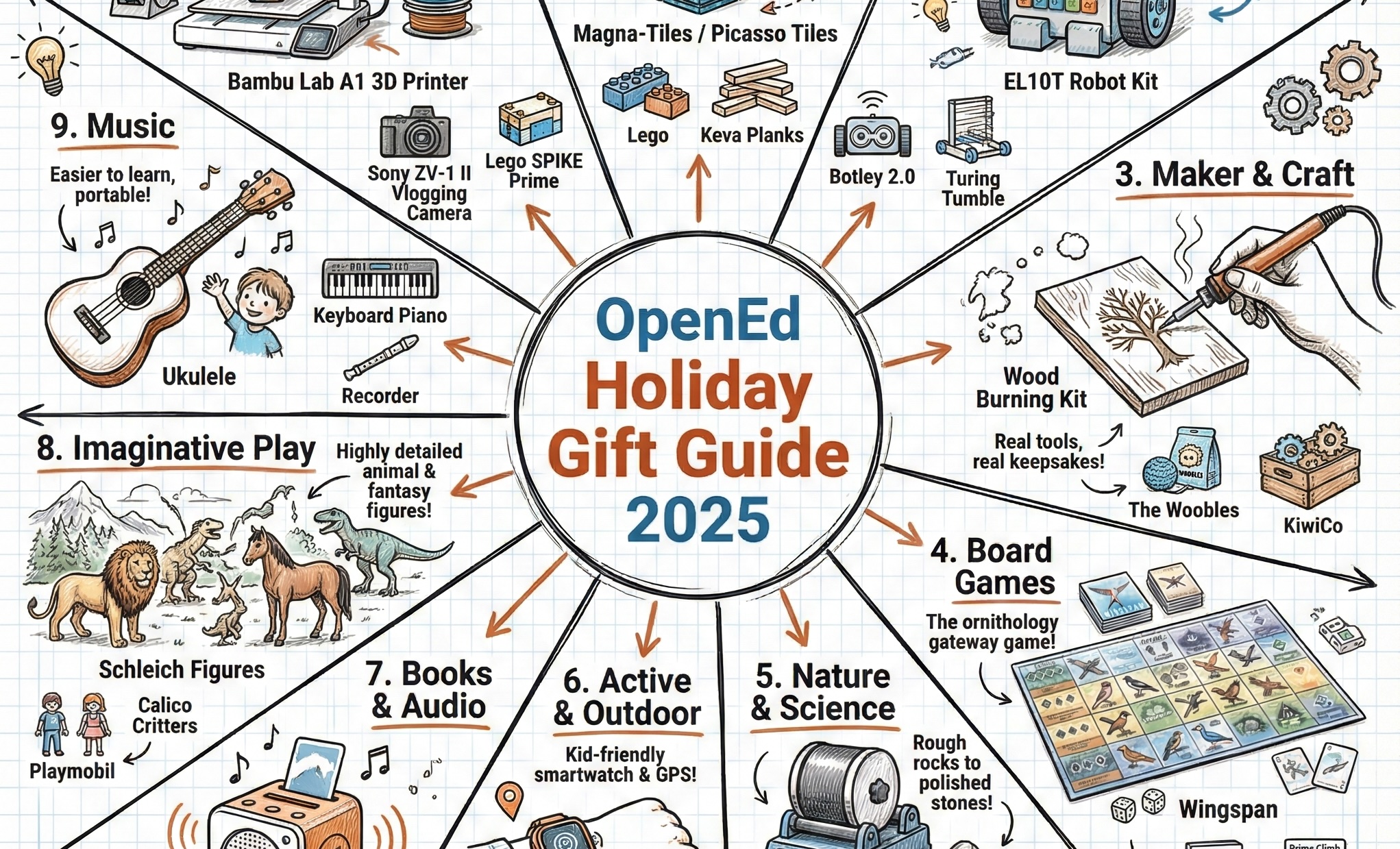

Subscribe to The OpenEd Daily

Join 20,000+ families receiving curated content to support personalized learning, every school day.

.webp)

.avif)

.png)

.png)