.png)

The Great Unbundling: Virtual School in the Post-COVID Era

The Great Unbundling: Virtual School in the Post-COVID Era

The Great Unbundling: Virtual School in the Post-COVID Era

March 2020: Teachers broadcast from their kitchens. Kids stared into the void of Gallery View. Parents became unpaid IT support, printing worksheets and resetting passwords.

Virtual school wasn't working.

Fast forward to 2025: A seventh grader in rural Idaho takes AP Calculus online and scores a 5. A dancer in California attends a rigorous virtual prep school while touring with her company. And a kid in Montana learns marine biology from an actual marine biologist in Florida, thanks to Starlink and the internet.

Both the 2020 version and 2025 version can be broadly described as "virtual school." But the experiences are worlds apart.

The difference has nothing to do with the underlying technology or internet speeds. It's about what virtual learning makes possible.

Despite the bad taste left in our mouths, thousands of families are discovering that early-pandemic Zoom school wasn't representative of what virtual school can be. A parallel ecosystem is emerging—not as a complete replacement for other forms of education, but as a significant component of a more open education that embraces the best that every approach has to offer.

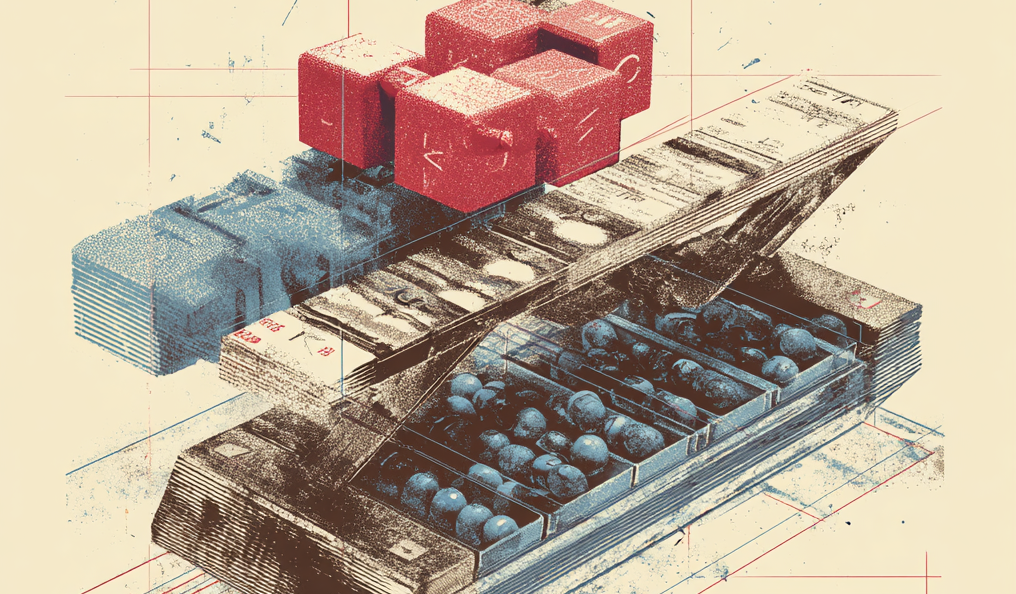

From One-Size-Fits-All to Unbundled

Before 2020, virtual schools existed primarily as a single product: complete K-12 programs offered online. Connections Academy, K12/Stride, and state-run programs served a specific niche—families who couldn't access traditional schools due to location, health issues, or schedule constraints.

These weren't homeschoolers in the traditional sense. They were families who wanted "school" but needed it delivered differently—usually at home. A ranch family in Wyoming. A child with chronic illness. A military family moving every two years. The model worked for them: enroll, receive curriculum, follow the schedule, and get a diploma.

But this all-or-nothing approach left gaps.

What about the student athlete on track for NCAA scholarships who needed rigorous academics on a more flexible schedule?

Or families who liked their local school for some subjects but not others?

Over the last decade, education has witnessed what some call "the unbundling of education." Families can now assemble learning experiences from multiple sources based on what their child actually needs—not a one-size-fits-all package.

Michael B. Horn, education theorist and co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, frames the shift as moving from "which school should I choose?" to "what combination of resources will work for my child?"

Homeschool parents pioneered this approach, mixing and matching curricula for decades. But the trend is spreading. Some schools now offer virtual courses as supplements (take AP Chemistry online, but still play in the local school band). Florida Virtual School's "Flex" program serves over 200,000 students taking individual courses while staying in their local schools for the majority of their coursework.

Other programs target specific needs. Subject, for example, is ideal for gifted student athletes who need NCAA-approved high school coursework that doesn't chain them to a desk for six hours a day.

And then there's the full unbundling—families architecting a complete education from multiple building blocks in what Outschool founder Amir Nathoo calls "networked schooling” (what we call “open education”).

Three Modern Approaches to Virtual School

While traditional schools struggled with Zoom in 2020, educators building virtual learning had been asking a different question for years: What can this medium do that the classroom can't?

1. The Media Model

Michael Vilardo, founder of Subject, watched the pandemic from a unique vantage point. He'd just spent $70,000 on an MBA at UCLA—"the worst learning experience of my life" on Zoom.

"I wasn't learning. I wasn't networking. I wasn't growing," he recalls in a TEDx talk. "On one end of my apartment, my wife was working a remote job, making six figures, waking up at 11:00 a.m. On the other, I was in a $70,000 a year MBA program, getting nothing."

But every evening after those brutal Zoom classes, he'd watch Netflix. The Last Dance. Tiger King. "I would binge these shows, loving every episode. This is when I learned that storytelling is the best way to provide incredible teaching and learning."

The contrast was stark. Netflix and TikTok were engaging young people like never before. A $70,000 MBA program couldn't do it at all.

"That was the institutional equivalent of pointing a camera at a stage play and calling it a movie," Vilardo says. "The problem wasn't the underlying technology. It was the failure of imagination."

The issue was taking a 200-year-old system—bells, standardization, the Prussian model designed for factory workers—and simply moving it online.

Vilardo and co-founder Felix Ruano understood that Gen Z doesn't learn in 50-minute lecture chunks. They learn in the rhythm of YouTube and TikTok. So they built Subject as premium, credit-bearing courses delivered through five-minute video lessons with charismatic teachers who speak to the camera like trusted influencers.

The data backs the approach:

- 85% of students prefer video-first modalities over traditional lectures

- Video-based learning drives 66% more assignment completion and 53% higher exam scores

- For students from lower-income backgrounds, graduation rates went from 81% to 85%

Subject particularly serves a specific niche: student athletes on track for NCAA scholarships, competitive dancers, aspiring musicians—students who need rigorous, accredited coursework but can't afford to be chained to a desk seven hours a day. The asynchronous, time-efficient model lets them complete their academics in focused blocks, freeing up time for the pursuits that define them.

This approach also points toward a broader shift. Some traditional schools are embracing flipped classroom models: students watch high-quality video lessons at home in their preferred format, then class time becomes interactive—reserved for discussion, collaboration, and hands-on work. It acknowledges that the broadcast lecture, whether in person or on Zoom, may not be the highest use of collective time.

Vilardo is equally focused on teachers. Video-based learning saves teachers over 500 hours a year on lesson planning and grading. "Teachers are the heroes in society. We have to support them more than ever before."

2. The Community-Driven Model

While platforms like Subject prove that well-designed asynchronous learning can be effective for self-motivated students, decades of research point to a different truth for many learners: isolation kills engagement.

Ray Ravaglia's journey started in 1987, building one of the first computer-based AP Calculus courses at Stanford. In 1991, one seventh grader, five eighth graders, four ninth graders, and three tenth graders enrolled in his course took the AP exam. Six scored fives, six scored fours.

Over the next 30 years, he further honed what actually works.

Ravaglia found that when students worked purely self-paced, even gifted kids had dropout rates over 30%. Add regular live sessions where students could see each other? Attrition dropped to 2-3%.

"If we could connect them with other students, that's what would keep them engaged for years," Ravaglia explains. "When you've learned something new, when you find something cool, you need to have that interaction. And if it's missing, it's just not going to be compelling."

The pandemic provided a mass validation of Ravaglia's thesis. What failed in 2020 wasn't online learning—it was the emergency transposition of passive, lecture-based pedagogy onto Zoom. Schools took a model that already struggled with engagement and stripped away its one advantage: physical presence and peer connection.

Ravaglia's insight: education is fundamentally about relationships. Technology can enable those relationships, but it can’t replace them.

The same held for teachers. Those teaching purely self-paced courses would optimize their work down to three hours a day—and then quit. Teachers in synchronous classes, despite more work, never quit.

"They would be there year in and year out. They'd make these great relationships with their students."

This insight shaped Stanford Online High School in 2005 and now informs his work at Dwight Global. Classes are small seminars—averaging 13 students—that meet live via video. The model uses a flipped approach: students prepare asynchronously, but class time is for Socratic dialogue, debate, and collaborative problem-solving.

"If we had Star Trek transporters to beam kids into a seminar room and then beam them home, we would do that," Ravaglia says. "We don't, but video conferencing can approximate."

His advice to parents is direct:

"Figure out what's the problem you're solving and why you're bringing technology in to address it. And if you have a school nearby that you love, enjoy it, be happy. Most people don't."

Programs like Synthesis Tutor and Recess.gg build on similar principles, creating synchronous, community-driven learning experiences through collaborative games and problem-solving challenges. Students work together in real-time with peers of similar ages and interests, combining the engagement of gameplay with genuine intellectual challenge.

3. The Marketplace Model: Outschool

Amir Nathoo founded Outschool in 2015 with a radical thesis: create a marketplace where teachers could teach whatever they wanted, and kids could learn whatever they wanted.

The challenge was the classic marketplace problem—getting supply and demand when neither side will join without the other. Nathoo's solution: start incredibly narrow with gifted homeschoolers in the San Francisco Bay Area.

"We used the fact that this early adopter audience is highly networked—meaning the way they transmit information is through personal connections, Facebook groups, Yahoo mailing lists, a lot of word of mouth," he explains.

The team would approach tutors: "Why don't you list the class on our site and we'll get you others." Then they'd ask those parents who else they worked with, and keep building.

Seven years later, Outschool offers over 140,000 classes.

"It's like every teacher can spin up their own little one-room schoolhouse one day a week for six kids to do that one thing," Nathoo says. "And then the kid can kind of pop from this one-room schoolhouse to this one and to this one."

He calls it "networked schooling." His own son attends an alternative micro school in San Francisco and also takes Outschool classes.

This reflects how humans actually live.

"We don't live in a world where our entire existence is contained in one box and one set of networks," Nathoo points out. "We have our friends that we only do sports stuff with. We have our friends at church. We have our work friends. We have all these domains and spheres that overlap."

"We aim to treat all of our teachers as creative entrepreneurial professionals, which is what teaching is," Nathoo says. "Unfortunately there are so many roadblocks within the traditional system. When you remove those blocks and give them an option, many take it."

The Quality Question

Five years after pandemic Zoom school, we're learning to ask better questions about virtual education. But concerns still linger about the quality.

The question isn't "does online learning work?" It's whether a particular approach makes students more engaged—with the material, with ideas, with the world around them.

Does it create pathways to real-world opportunity and connection? Does it preserve or expand their curiosity?

By this measure, three insights have emerged:

1. Relationships trump delivery method

When students met live and formed friendships, they created accountability beyond the teacher. "If someone doesn't show up, their classmates notice. They text each other," Ravaglia explains. In asynchronous classes, if you stop engaging, people often don't notice until term ends.

2. Not all screen time—or asynchronous content—is equal

"Just watching YouTube is completely different to building a virtual world or learning a tool or building with others," Nathoo insists.

The difference shows in how kids emerge. "If a kid has spent an hour watching YouTube videos, they have a different look on their face and need detox time. Versus coming away from Outschool classes brimming with creativity and excitement."

This matters especially for asynchronous learning. Done poorly, it becomes like those driver's ed courses where you click through slides as fast as possible. Done well—like Subject's storytelling-driven video lessons or engaging interactive simulations—it becomes efficient without sacrificing depth.

The most successful virtual learning blends digital and physical: movement breaks, cooking together, hands-on projects, local co-ops for science labs, sports teams. Technology should create flexibility for more real-world experiences, not fewer.

3. Parents design, not consume

The shift to virtual learning changes the parent's role. You're not responsible for being the expert or the primary instructor, but you're also no longer passively accepting what's provided. Instead, you're actively assembling and curating resources.

A museum curator doesn't paint every painting—they decide which works to display and what story they tell together. You don't have to be the calculus teacher; you have to find the one that clicks with your kid.

For families where the local school works for some needs, Ravaglia suggests part-time enrollment. Do English and Humanities at school, then go online for advanced math and science. Or the reverse—rigorous academics online but play in the local school band.

Virtual school also provides an alternative to pure homeschooling—especially for high school students, independent learners, or those whose primary calling is dance, a sport, or another pursuit. But it's becoming something more: a way for students to master academics efficiently and reclaim time for what they're passionate about.

Alpha School, for instance, experiments with helping students complete traditional coursework in significantly less time, freeing up hours for exploration, creation, and real-world experience.

The Spectrum of Options

The ecosystem now includes:

Traditional full programs like Connections Academy and Stride, offering complete K-12 programs

Supplemental courses like Florida Virtual School Flex (200,000+ students taking individual courses while staying in local schools)

Time-efficient curricula like Subject, using short-form video lessons for students who need to balance academics with other pursuits

Marketplace platforms like Outschool (140,000+ classes), where kids access specialized instructors from anywhere

Community-driven learning like Synthesis Tutor and Recess.gg, combining synchronous participation with game-based problem-solving

AI-enhanced tutoring like Khan Academy with KhanMigo, adapting to each student's pace and knowledge gaps

Customizable programs like OpenEd Academy ($2,900-$3,500/year), where families choose curriculum and pace for each subject

The common thread: none of these are trying to be everything for everyone. They're solving specific problems for specific families.

What Virtual Learning Makes Possible

The future of education isn't about choosing between virtual and in-person. It's about recognizing what each makes possible.

Virtual learning, done well, can:

- Give student athletes, dancers, and musicians rigorous academics that travel with them

- Connect gifted rural students with intellectual peers from around the world

- Let a high school student complete coursework in three focused hours, then spend afternoons apprenticing with a local architect

- Provide multiple pathways for shy or introverted students to connect with teachers and peers

- Enable families to mix and match—AP Calculus from Stanford, marine biology from that instructor in Florida, band at the local school, Wednesday afternoons at the community makerspace

"Virtual" doesn't need to be a dirty word. Technology is a tool—a means to an end—that, used thoughtfully, can give students access to knowledge, community, niche courses that nourish their interests, and something increasingly rare: their time back to pursue what makes them come alive.

"It's truly exciting to think about what could happen if a generation of kids are educated by creative entrepreneurial teachers who are genuinely passionate about their subjects and given the freedom to teach the way they always wanted to teach," Nathoo says. "That sounds like the future to me."

Stop asking "virtual or in-person?"

Instead, ask “What combination of resources—online and offline, synchronous and asynchronous, formal and informal—will help my child thrive?”

Subscribe to The OpenEd Daily

Join 20,000+ families receiving curated content to support personalized learning, every school day.

.webp)

.avif)

.png)

.png)